Six year old Suman worked at scratching shapes and lines on the metal pipe with a piece of cold charcoal from a lane way fire. Her baby sister Nandini and her two year old brother Prem sat nearby playing with rocks. As I rushed by I took a quick backward glance and saw Suman dangling Nandini by one arm over the perch they were sitting on. I backed up half a step as Suman’s grasp on Nandini gave way and I awkwardly grabbed Nandini while shifting my bag to accommodate her little body against mine and continued on my way. Suman and Prem followed close behind holding on to my pant leg. Another morning in the slum was about to begin.I feel at home in this community and I am used to seeing small children tending to even smaller children. I don’t wince as much when the kids offer me food with filthy hands or when I am invited into homes and notice the women don’t use soap to clean their dishes or wash their hands before they prepare food just after they wiped the snotty nose of a child with a corner of their sari. I casually step over children pooping in the lane ways, my quick movements scattering chickens with hardly any feathers left, almost ready for the stew pot. Focusing on other matters I tend to overlook the difficulties of getting through the day, for us and obviously for the people who live here. We are often asked questions about how people live here, how they manage, what is it like to be there everyday. Describe it. Laying a magnifying glass over the community I will try to convey the details of their lives in questions and answers.

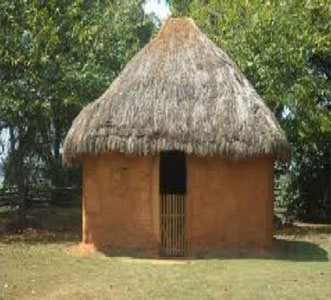

What is the size of the homes and what are they made of?

A large home measures 10 feet by 25 or 30 feet, made of stacked, porous brick with a roof of asbestos sheeting layered with plastic kept in place with tossed bricks and heavy objects. The inside walls are coated with a thin veneer of cement often painted a pale pink, blue or yellow. A small home measures barely 10″ by 10″, with many being smaller. These dwellings are made of scavenged materials cobbled together using rope, tape, nails, and globs of cement over a hard mud floor. Doors swing off kilter held in place with mismatched hinges weighted by oversized padlocks. The inside of the homes smell of dank, old, stale air moved around by fans with blades covered in layers of city dust and grime.

What do the homes look like inside?

Clothing and personal items hang on hooks or nails and ubiquitous plastic bags hold important papers. There is one shelf, maybe two to hold sleeping mats. If the home is large there will be a metal cupboard to stash personal belongings. Most homes have a metal rack to hold dishes above the floor and large metal bins for flour and sugar. Worn plastic bags hang on walls holding spices, ginger and maybe extra tomatoes. Generally there is no space for furniture. A water spout sticks out of the wall where a hole in the slanted floor allows the water to drain. In this 2 by 2 area there is a half wall to divide the bathing space from the rest of the room. The floors, although swept, always feel gritty and dust clings to the pads of feet.

Do they have running water?

Yes, this community is lucky. Because they live on a water pipeline, water is available from taps up and down the lane ways and inside some homes, although the plumbing is rudimentary. Water drips constantly and we flinch when we see water gushing into overflowing buckets, covering the ground making dark, sludgy puddles, instead of being conserved and coveted. Educating the community about conserving water is an ongoing dilemma. It is the one thing they have a lot of.

How do they wash their clothing?

Up and down the lane ways, we can hear the thwap, thwack, and thud of women beating their sudsy laundry on rough cement patches outside their homes. Buckets are filled with water, clothing is dunked into it, then removed to the cement. Clutching a bar of detergent, the women use all their muscle to scrub, wring out and scrub again. The rinse cycle begins by splashing cupfuls of water over the sudsy laundry, pressing it hard and then starting the process over until the water runs clear. Imagine washing 6 meters of a sari this way, plus sleeping sheets almost daily.

Where do they dry their laundry?

On bamboo poles stuck in intervals along the pipeline, on barbed wire fencing, or on wire or string attached to the outside walls of a home. The vibrant colours of the clothing strung up to dry provide a visual collage as far as the eye can see.

How to they cook their food?

Most homes use kerosene burners (a few families have gas cylinders and two burner cook top). Cooking fires stoked with scavenged wood, garbage and plastic pollute the lane ways with toxic fumes, but save on kerosene. A ring of broken concrete, rocks, or pieces of brick form a raised surface to contain the fire and provide a place to put a pot or kettle. Kids often tend these fires, chucking in bits and pieces of garbage, poking the fire expertly with found sticks. Food is prepped outside in the lane way or on the floor of the home.

What do they eat on a daily basis?

Most families eat a diet of dal (lentil stew) with rice or chapati. Small bits of onion, garlic and tomato are added to give some extra nutrition. Meat or fish is purchased for special occasions if at all.

What do they sleep on?

Some homes have raised wooden platforms covered with handmade blankets to provide some comfort but most families sleep on plastic woven mats called chettais laid on the bare floor or on a layer of handmade quilts. Some people sleep in the lane ways on charpoys which are simple cots made of latticed nylon strapping.

Where do they buy their food?

They purchase their food from vendors who ply the lane ways with primitive, wide, wooden carts selling mostly potatoes, onions and tomatoes. Sari’s, children’s clothing, glass bracelets, fish, spare parts for kerosene burners, pani puri, are carried into the community on the heads of vendors who chant their sales pitch as they march down the pipeline. Some families shop in the streets of Saki Naka doing errands before they fetch their young children from school.

Where do they bathe?

In the morning the lane ways are dotted with men squatting, taking open-air bucket baths clothed from the waist down, completely covered in a froth of suds, creating soapy rivers to cross. The women bathe in private in the corner of their homes in the same small area they use to wash dishes and to urinate.

Where do they go to the toilet?

There are squat toilets used for defecating by men and women in a few areas of the slum used by hundreds of people and cleaned by sloshing water in the cubicle, the stench being almost unbearable. Carrying a vessel (an old paint can, a plastic jug with the top cut off, a garbage pail) the person will trod the lane way, spilling water as they walk to line-up for their turn at the squat toilet. The water is for washing themselves. No toilet paper is ever used. Children simply pull down their pants and go to the bathroom in the lane ways or the gutters that flow past every home. Some mothers put out newspaper or leaves for the child, rolling them up and tossing them away. Older children and adults are also seen squatting on the large garbage pile, or on the road just outside the slum boundary.

Where does their garbage go?

About every hundred yards there is a pail or container for garbage. There is a garbage collection boy who empties these pails and takes the garbage to bins on the roadway. Bags of garbage are also thrown into a small fenced area near a group of homes. Littering is prevalent and there is little concern for accumulated garbage in the lane ways or in most of Mumbai. Civic pride is lacking both in the slum and outside the slum as there seems to be little incentive to take pride when there are millions who don’t care and a government that doesn’t enact fines or punishment for littering or throwing garbage on roadways or vacant lots. The best that can be said about garbage is the scavenging mentality of slum dwellers. If something can be used in any way it isn’t thrown out. Cardboard, metal, bricks, sand, paper, rubber, styrofoam are all used to make something else if possible.

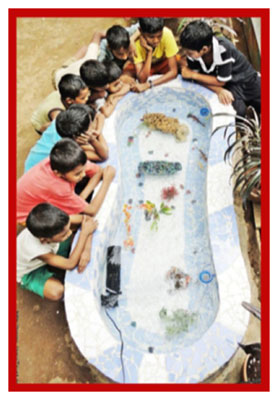

What do the kids play with?

If necessity is the motherhood of invention, the kids who live in the slum get top marks for ingeniously making toys out of refuse. Give them some tape and an old tire and they will make a drum. Hand them some plastic, some skinny sticks and some twine and they will make a kite; broken styrofoam packaging will become a percussion instrument tied with scavenged twine around the neck or it will be cut and shaped into a boat to float on murky puddles or in the gutter. Charcoal from last night’s fire is used to draw shoppings games on the odd piece of smooth cement; the pipeline, smooth and enormously round becomes a slide and a place to run. There are a few rickety bicycles, and of course the new cricket pitch in the garden used by boys of all ages. A rousing game of marbles draws spectators to huddled groups of boys. Drawing and painting classes are provided in the school with access to art supplies. Toys are donated by corporations for small children.

What do the men do?

Working outside the slum is common for most of the men unless they are old, invalid, alcoholic or lazy. They are rickshaw drivers, factory labourers, mechanics and some work in offices. They leave the community freshly bathed wearing clean, expertly pressed clothing because to appear disheveled in public is frowned upon. Parents often send their children clutching clothing to be ironed to the quiet, meticulous man who irons on a makeshift table in front of a small shop in the community. For a few rupees, he expertly presses shirts and trousers and folds them into a neat parcel, ready for pick-up. Expert haircuts and close shaves are supplied by the wandering barber while squatting in the lane way.

Where do kids go to school?

The school in the slum is for kindergarten. Older children go to municipal school or private schools taught in English, Hindi or Marathi within walking distance from the community. All schools charge a fee and many of the kids require sponsorship. The municipal schools are noted for their lack of substance, uncaring teachers, and shoddy administration. Some are without running water. Most schools are just a building with no school yard and overcrowded classrooms with kids shoulder to shoulder. Uniforms are worn, girls must wear their hair in braids looped once and tied with ribbons, boys are to wear their hair short and neat.

Do the women work outside the slum?

Women without husbands, or whose husbands are sick must work outside the slum to provide for their family. The jobs available to uneducated, illiterate women are cleaning or labour jobs with abysmal pay. (The new Girls Can Be room has enabled over 20 women to earn money by working on sewing projects allowing them freedom to do piece work in their homes while they care for their children). Women spend their days winnowing rice to to pick out the rocks (cheap rice is often weighted with rocks and pieces of brick), washing clothes, making dal and chapati, sweeping the lane way outside their doors, and sipping chai in the late afternoon. Most of the women don’t know how old they are and the ones who do look at least 10 years older. Sun, stress, poverty, poor diet and no exercise ages them prematurely.

Who looks after kids whose parents leave the slum during the day?

It is our observation that once a child can walk, he or she is often left alone for the day to wander the community, possibly with a slightly older sibling alongside. These kids are tough, resilient, and don’t break easily.

What do they do for medical care?

Home remedies are often the first line of defense for ailments, including the use of an exorcist to get rid of evil spirits which may be causing the illness. Doctors are visited if absolutely necessary. Families often require assistance to pay the doctor’s fees. Health camps are funded by a corporation once a month at the school. This is where small concerns can be discussed with a doctor and if required, free medication is dispensed. Many of the women are overweight but probably malnourished. Diabetes and heart disease can be attributed to the liberal use of salt, oil and sugar in the food they cook and consume. Rat bites, malaria, typhoid fever, dengue, TB, AIDs, lice, boils, cataracts and cuts that become septic are all daily health concerns.

What religions are in the slum?

A melange of religions including Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims and Christians live side by side, each religion observing sacred rituals, holidays and pujas without interference. Women wear burkas, salwar kameez and sequined saris.

How long do families stay in the slum?

Some of the families have lived here for over 25 years. Others come and go as job prospects or family matters take them to other parts of Mumbai or back to their villages if they can’t afford the rent in Mumbai. New dwellings sprout up daily, adding to the already bulging community.

Do they have arranged marriages?

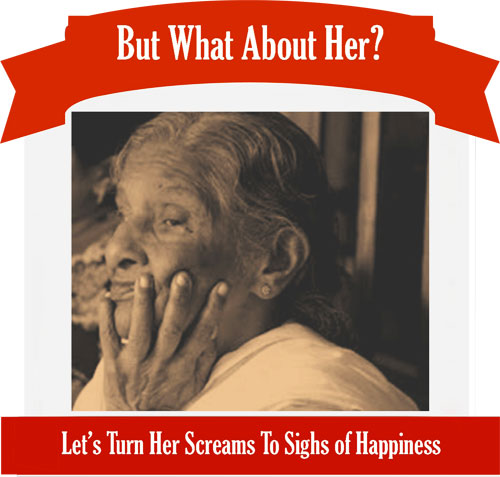

Hindu families (and some Muslim parents) arrange marriages for their children. Girls will be matched as young as 17 while the parents of boys wait until their son is over 20. Dowries are common in slum communities and put great financial strain on the parents of girls. Once married, girls leave the home to live with their husband’s family. If the husband’s family is greedy or dislikes the girl more dowry money can be insisted upon and the girl may suffer at the hands of her in-laws or her husband if extra dowry money is not paid. Most families won’t take their daughters back insisting they have to adjust to their new lives. This causes a great deal of unhappiness and anguish for the daughter when her parents start the search for a husband. There is wide-spread physical abuse of wives in this community. Alcohol, dire financial stress and living in a community where abuse of a wife is tolerated is like a pool of grease staining the whole community and the interactions within. We can only hope the the next generation of girls will be more educated, intolerant of abuse and aware of their rights as women and people.

Where do they give birth?

Women pre-arrange to give birth at at a clinic which is more sanitary and provides the formal recorded details of the birth.

Do they own their homes or rent them?

Slums are illegal and are situated anywhere there is space to build, between buildings, on municipal property, private property and adjacent to roadways, train tracks and on land by the airport. Slum dwellers don’t own the land, but can get paperwork as an owner of a dwelling (important if the slum is bulldozed as only those with paperwork will get a Slum Rehabilitation flat built by the government). Slumlords, who, through corruption manage to own a number of dwellings rent bare tin huts for exorbitant rates to newcomers and cruelly evict families who miss payments for reasons beyond their control.

Do they pay bills?

Yes, they pay electricity bills and water connection fees to the BMC.

What modern conveniences do they have?

A coveted refrigerator sits proudly in very few homes. Most homes have small televisions with grainy pictures and tinny sound sitting high up on dusty shelves. A few women have electric mixies (small blenders). Some of the men who have jobs that pay well have a small motorbike.

Do they travel outside of Mumbai?

Most people who live in the slum have come to Mumbai from other states or small villages near Mumbai so they may return to their place of birth to visit family members once a year. Slum dwellers often borrow money from moneylenders at high interest rates to enable them to pay bills or medical fees or leave Mumbai for various reasons.

What is the literacy rate?

The majority of adults living in the slum are illiterate but may be skilled at a trade. Many don’t know how old they are. Although Hindi is understood and spoken, most of the people in the community speak and understand Marathi, the language of Maharashtra (the state). Some of the children go to English Medium schools and can shift from English to Marathi with relative ease. Johnnie, who is about 12 is my translator in frustrating situations.

Is there hope and happiness despite the conditions and poverty?

Each family has problems compounded by dire poverty, caste issues, sickness and even by the hierarchy in the slum, but despite the prevalent problems that will continue to persist, there are smiles and belly laughs, pujas and prayers, celebrations, excitement around births and uneasy silence surrounding a death, all shared by a community of many religions. Even as tempers flare, children tumble with each other in play, find meaning in the meaningless, have energy and excitement after sleeping curled up like a puppy on a cement floor, and yes, the adults have hope, if not for themselves, they believe anything is possible for their children.

Shiraj and I meandered through the slum past the makeshift homes, sometimes having to walk single file while squeezing between huddled children, the jagged metal of the unused train tracks that bisect the main lane way and the hulking metal pipeline. Speaking english, he asked me what I thought of his community. I replied, I think it is hard to live here. No, not really, he said. I don’t think it is too hard. We are used to it so we are not bothered by what you see. Before I could say anything more, he deftly changed the subject. Do you like pie? he enquired. I answered, probably too earnestly, Uh, yes, I love pie, especially lemon pie! He told me he would make me a lemon pie during his bakery class at the vocational school he attended. A few days later Kane and I sat cross legged on the gritty floor in his family’s tiny home, the smell from the burbling gutter seeping into our noses, and dug into a delicious lemon pie. Shiraj apologized because the pie didn’t have meringue. He said the meringue would have melted on the two hour journey home, the uncovered pie held aloft over his head while he fought for space in the overcrowded train. It was the best pie I have ever eaten, and instead of meringue I had a dollop of perspective.